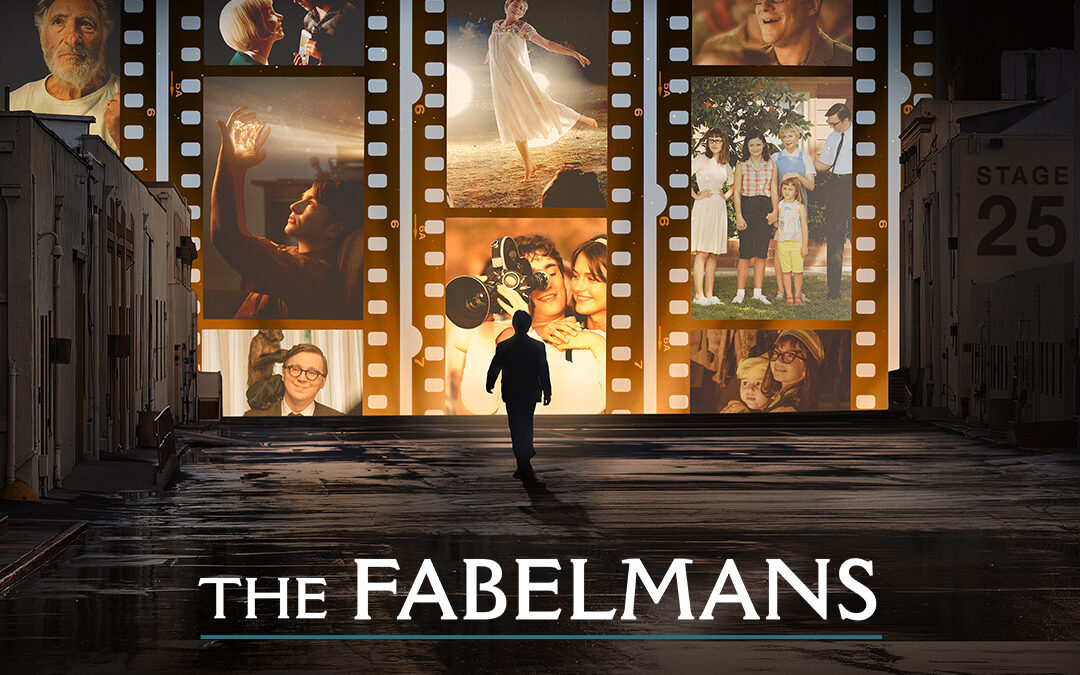

Rated PG-13

Starring Michelle Williams, Paul Dano, Gabriel LaBelle, Seth Rogen, Judd Hirsch, Jeannie Berlin, Julia Butters, David Lynch

Critical Rating: ***** of *****

Austin Family Family-Friendly Rating: **** of *****

Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans is the best movie of the year – a wonderful ode to the joy and pain of making movies, a thoughtful and moving recollection of youth by one of cinema’s greatest storytellers, and, above all, an immensely entertaining motion picture. The film recalls another auteur filmmaker’s tribute to the power of cinema, Martin Scorsese’s Hugo (2011), and falls into a recent sub-genre of top-tier directors reflecting on their upbringings (James Gray’s excellent Armageddon Time also fits into this category). But The Fabelmans has a special quality all its own and offers us the genesis of the broken family theme that’s present in so many of Spielberg’s indelible films.

Sammy Fabelman (played by Mateo Zoryon Francis-DeFord as a boy, then by Gabriel LaBelle as a teenager) attends his first movie with his parents, Mitzi (Michelle Williams) and Burt (Paul Dano), at the age of six. The film is Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), and the images onscreen are seared into Sammy’s brain – along with a desire and need to recreate those images within his own home (particularly a rousing train crash sequence). When Sammy receives a train set for Hanukkah (along with an 8mm camera lent to him by his mother), he goes about shooting his first home movie.

The Fabelmans offers many ideas as to why a child might want to make films, but Sammy’s mother is able to identify perhaps the most enlightening reason – Sammy wants to exert some kind of control over the train crash. Mitzi understands this desire more than Burt, as she was a piano prodigy who gave up her dream, we presume, to raise her children (Sammy has three younger sisters).

Although Sammy’s need to “control the train crash” isn’t linked to tragedy initially, it’s not long before events in his family life spin completely out of his control, and the only place for him to turn is to his filmmaking.

After the death of Mitzi’s mother, Burt asks a teenage Sammy to edit together a home movie from their blissful family camping trip. Burt senses there’s something wrong in his marriage, and he hopes Sammy’s film might lift Mitzi’s spirits. Sammy, a bit dejected that he has to temporarily put aside his ambitions to shoot an action-packed war movie with his classmates, goes about editing the camping trip footage – and, in the process, discovers hints of possible marital infidelity in the background of certain frames.

Spielberg is careful to show empathy for both Mitzi and Burt during the slow dissolution of their marriage. There are no bad people in this movie, only flawed individuals trying to navigate an uncertain world. There’s a deliberate parallel here to Spielberg’s own filmography, in which his brilliance at making escapist entertainment in the early part of his career (think Jaws, Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T.) eventually gave way to the filmmaker tackling weightier, sometimes quite personal subjects (namely, depictions of the Jewish experience in films like Schindler’s List and Munich). And it’s taken him 75 years to finally edit together his own home movie, and it was worth the wait.

I couldn’t help but identify with the film’s final scene, in which Sammy – now out of high school and about to start a job at CBS in Los Angeles – waits in the office of one of his heroes, the legendary director John Ford (played by director David Lynch in a terrific cameo). Sammy has now come full circle and is face to face with the man whose films made such an impression on him as a young person. Without being too corny about it, I feel like I’ve sat in that office, too, staring wide-eyed at the poster collection of my hero (in my case, Martin Scorsese). Look, I’m no Spielberg and I never will be, but the feeling conjured up by this scene rings completely true. It’s about the giddy sense of a future where the possibilities are endless, where one’s lifelong artistic practice may one day pay off, where the horizon is always just ahead – and, ideally, framed correctly. That last one may only make sense once you’ve witnessed the final shot of The Fabelmans.

If The Fabelmans is still playing in a cinema near you, I cannot implore you enough to go see it. The adult audiences on which this kind of film depends for survival are simply not showing up at the cinema, despite the numerous exceptional entertainments released in the last year (including Spielberg’s own West Side Story, which should have been a powerhouse at the box office). The Fabelmans truly feels like a last stand for cinema. Yes, you can catch it on VOD, but for a movie that’s about the power of the moviegoing experience, it’s simply not the same thing. And, to put it bluntly, studios are going to stop making serious, thoughtful, intelligent movies like these if folks don’t show up to see them.

The film is rated PG-13 for some thematic material (the divorce of Mitzi and Burt) and the anti-Semitic language used by Sammy’s bullies. Everything is depicted in such a tasteful, empathetic way that I’d say there’s nothing objectionable here for children over ten years old. In many ways, The Fabelmans is one of the best films ever made about a family.

Review by Jack Kyser.